From high mountain ranges to vast desert plains and fertile coastal areas, Iran is a land of contrasts. Iranians often explain the profound spirituality of their music and poetry as a response to this landscape as well as to the country’s turbulent history.

Rooted in a rich and ancient heritage, this is music of contemplation and meditation which is linked through the poetry to Sufism, the mystical branch of Islam whose members seek spiritual union with God. The aesthetic beauty of this refined and intensely personal music lies in the intricate nuances of the freely flowing solo melody lines, which are often compared with the elaborate designs found on Persian carpets and miniature paintings.

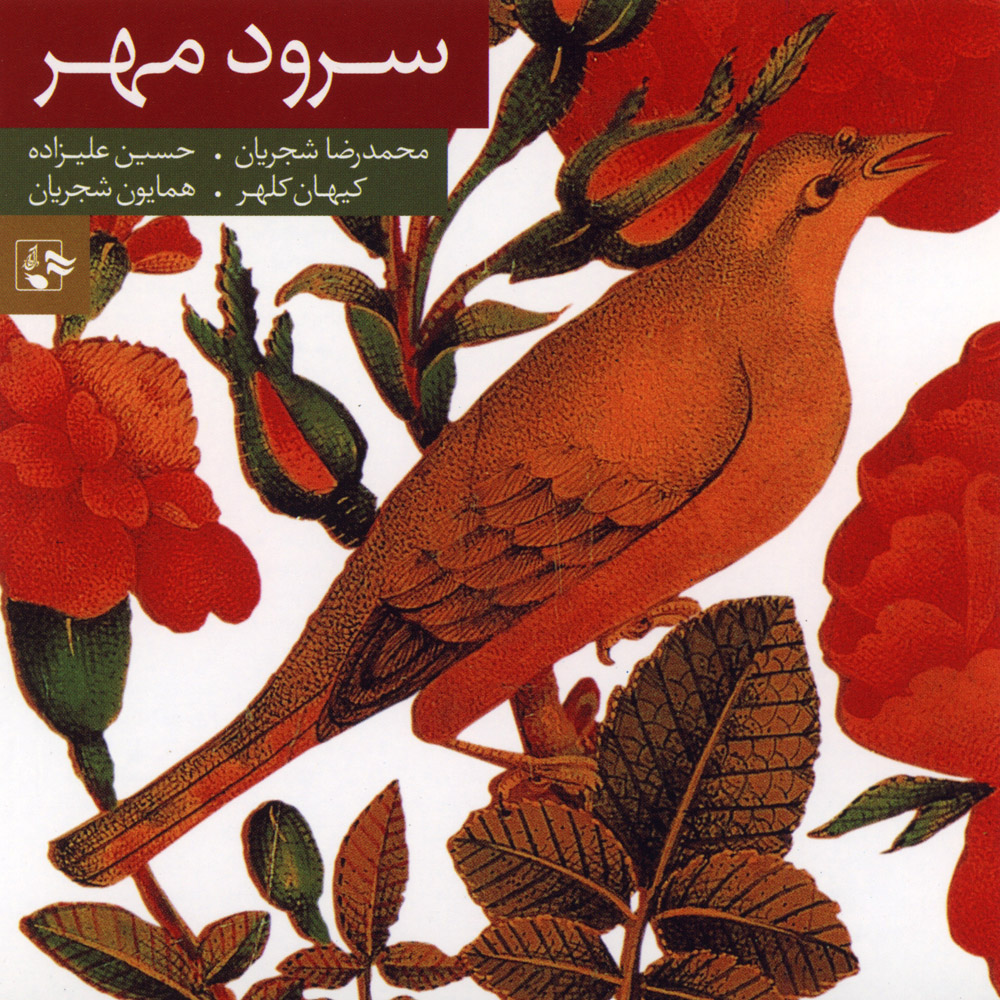

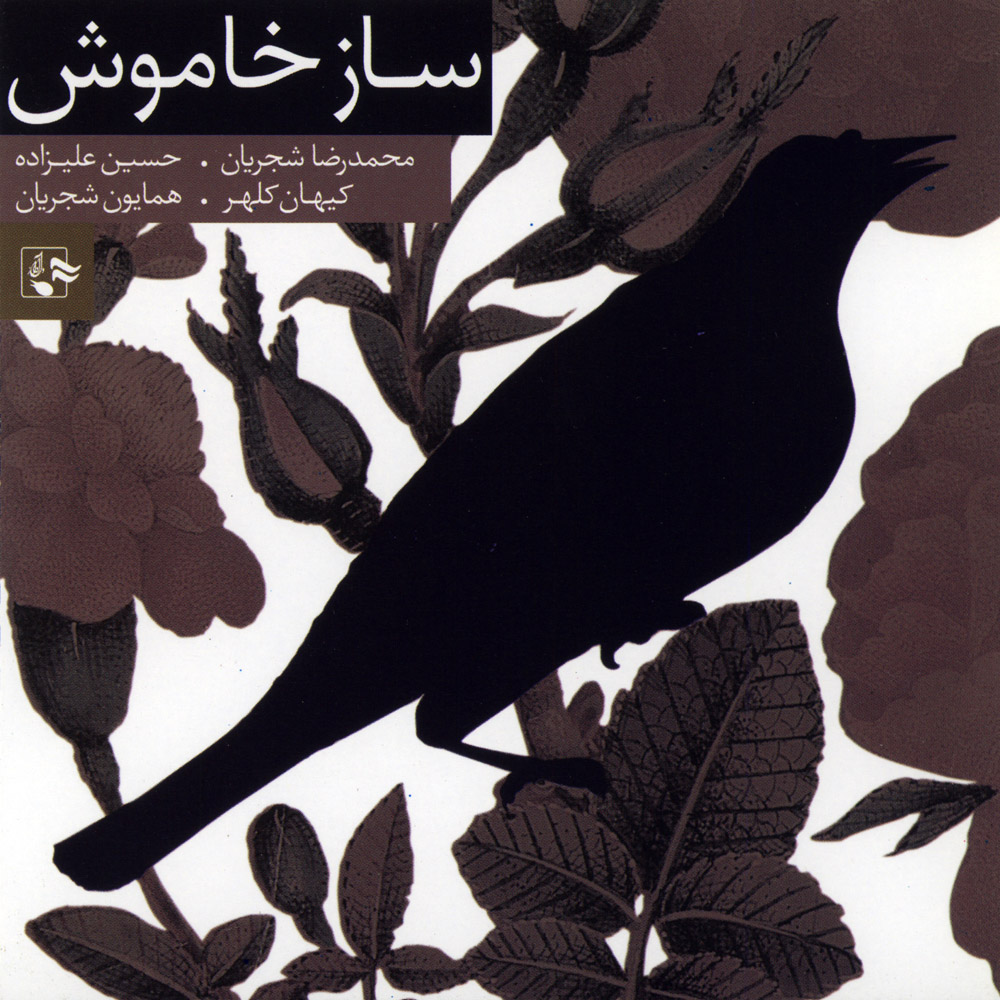

Creative performance lies at the heart of Persian classical music. The importance of creativity in this music is often expressed through the image of the nightingale (bol bol). According to popular belief, the nightingale possesses the most beautiful voice on earth and is also said never to repeat itself in song. A bird of great symbolic power throughout the Middle East, the nightingale represents the ultimate symbol of musical creativity. To the extent that Persian classical music lives through the more or less spontaneous re-creation of the traditional repertoire in performance, the music is often described as improvised.

The musicians themselves talk freely of improvisation, or bedaheh navazi (lit. “spontaneous playing”), a term borrowed from the realm of oral poetry and which has been applied to Persian classical music since the early years of the twentieth century. Musicians are also aware of the concept of improvisation in styles of music outside Iran, particularly in jazz and Indian classical music. But as in so many other “improvised” traditions, the performance of Persian classical music is far from “free” – it is in fact firmly grounded in a lengthy and rigorous training which involves the precise memorization of a canonic repertoire known as radif (lit. “order”) and which is the basis for all creativity in Persian classical music.

Like other Middle Eastern traditions, Persian classical music is based on the exploration of short modal pieces: in Iran these are known as gushehs (lit. “corners“) and there are 200 or so gushehs in the complete radif. These gushehs are grouped according to mode into twelve modal “systems” called dastgah.

A dastgah essentially comprises a progression of modally-related gushehs in a manner somewhat similar to the progression of pieces in a Baroque suite. Each gusheh has its own name and its own unique mode (but is related to other gushehs in the same dastgah) as well as characteristic motifs. The number of gushehs in a dastgah varies from as few as five in a relatively short dastgah such as Dashti, to as many as forty-four or more in a dastgah such as Mahur. The training of a classical musician essentially involves memorizing the complete repertoire of the radif. Only when the entire repertoire has been memorized – a process which takes many years – are musicians considered ready to embark on creative digressions, eventually leading to improvisation itself. So the radif is not performed as such, but represents the starting point for creative performance and composition.

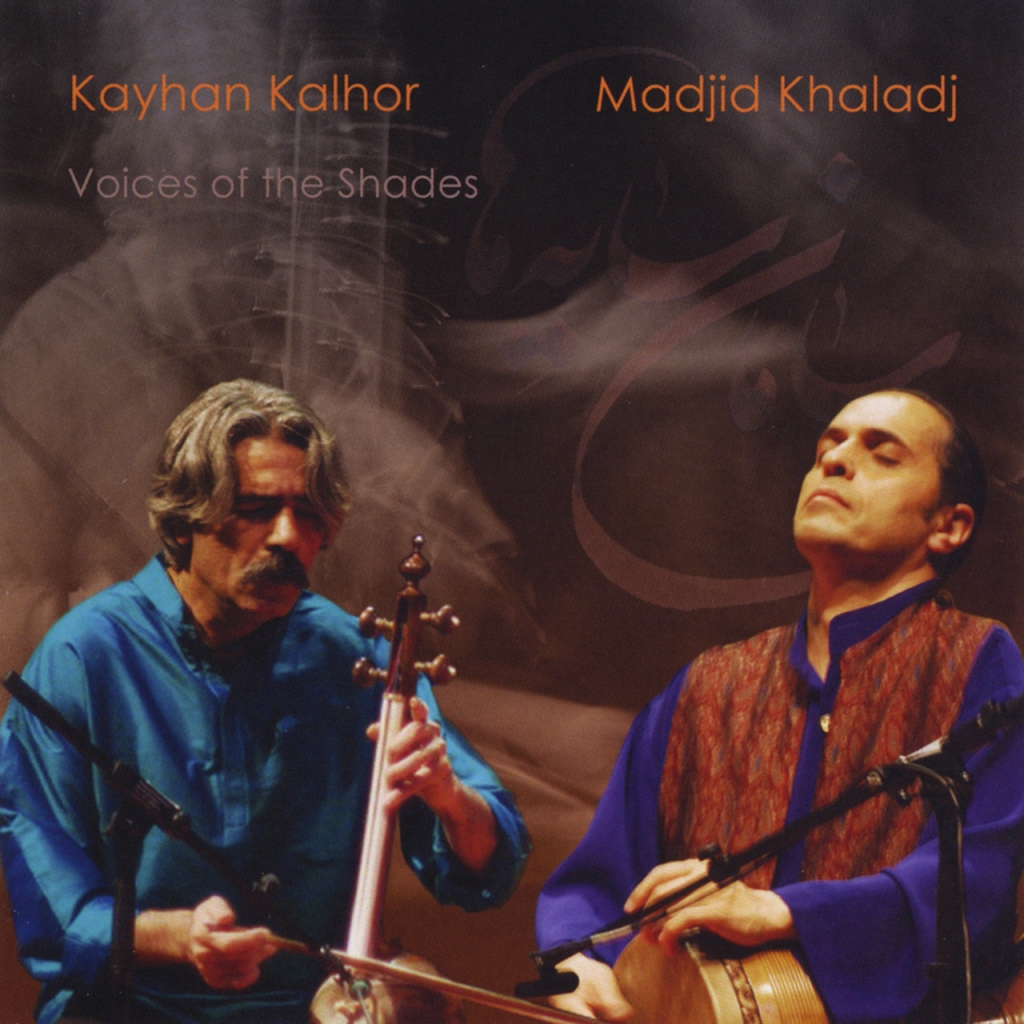

The complex detail of the solo melody line is of utmost importance in Persian classical music – there is no harmony as such and only an occasional light drone (in contrast with the constant underlying drone in Indian classical music). As such, Persian classical music was traditionally performed by a solo singer and a single instrumental accompanist – in which case the instrument would shadow the voice and play short passages between the phrases of poetry – or by an instrumentalist on his own. In the course of the last century it became increasingly common for musicians to perform in larger groups, usually comprising a singer and four or five instrumentalists (each playing a different classical instrument). Nowadays one can hear both solo and group performances.